How to reduce the impact of what we consume

Published: 6 Dec 2022

Think back to the last meal you had. Chances are, the food on your plate is better travelled than many of us.

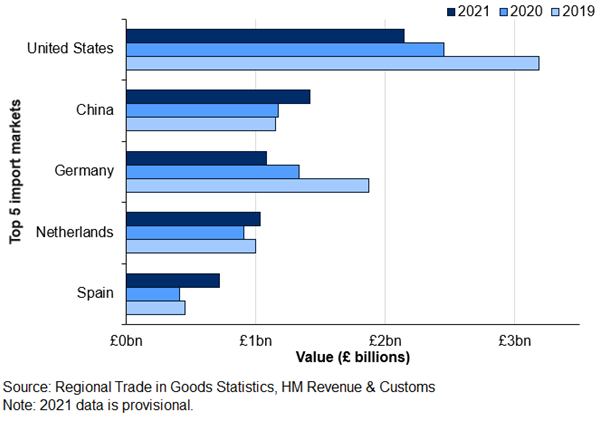

It may not be surprising that we import a lot of the goods that we consume in the UK. In 2021, Wales imported £16.1 billion of goods, an increase of £1.9 billion from the year before, the main country being the United States, followed by China and Germany.

Almost half of the UK’s entire carbon footprint comes from overseas emissions, but these figures haven’t traditionally been included in national reporting, despite only existing because of our consumption-based demands.

For much of our food, we often rely on countries in the Global South to provide us with products that aren’t optimally grown in our Welsh climate. Let’s look at an example. We are a banana-loving nation, consuming over 5 billion of them per year – that's 100 bananas per person! While these are predominantly imported from Columbia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and the Dominican Republic, it may surprise you that in 2021, we imported 8,934,021 kg of bananas from the Netherlands. While many of these may be re-exports, the Netherlands are leading the way when it comes to home-grown bananas.

The greenhouse-grown bananas are planted in pots with substrate made from coconut fibres – an innovative approach to combat soil-born fungi and bacteria which pose a threat to the crop worldwide. The company responsible are aiming to tackle these threats, whilst creating a sustainable circular process where the peels are also being used to create fibre and wood substitutes. As the carbon footprint of bananas is about 1.37kg of CO2 per kg, these emissions are mostly from transportation and primary production which could theoretically be reduced with innovative and sustainable approaches closer to home.

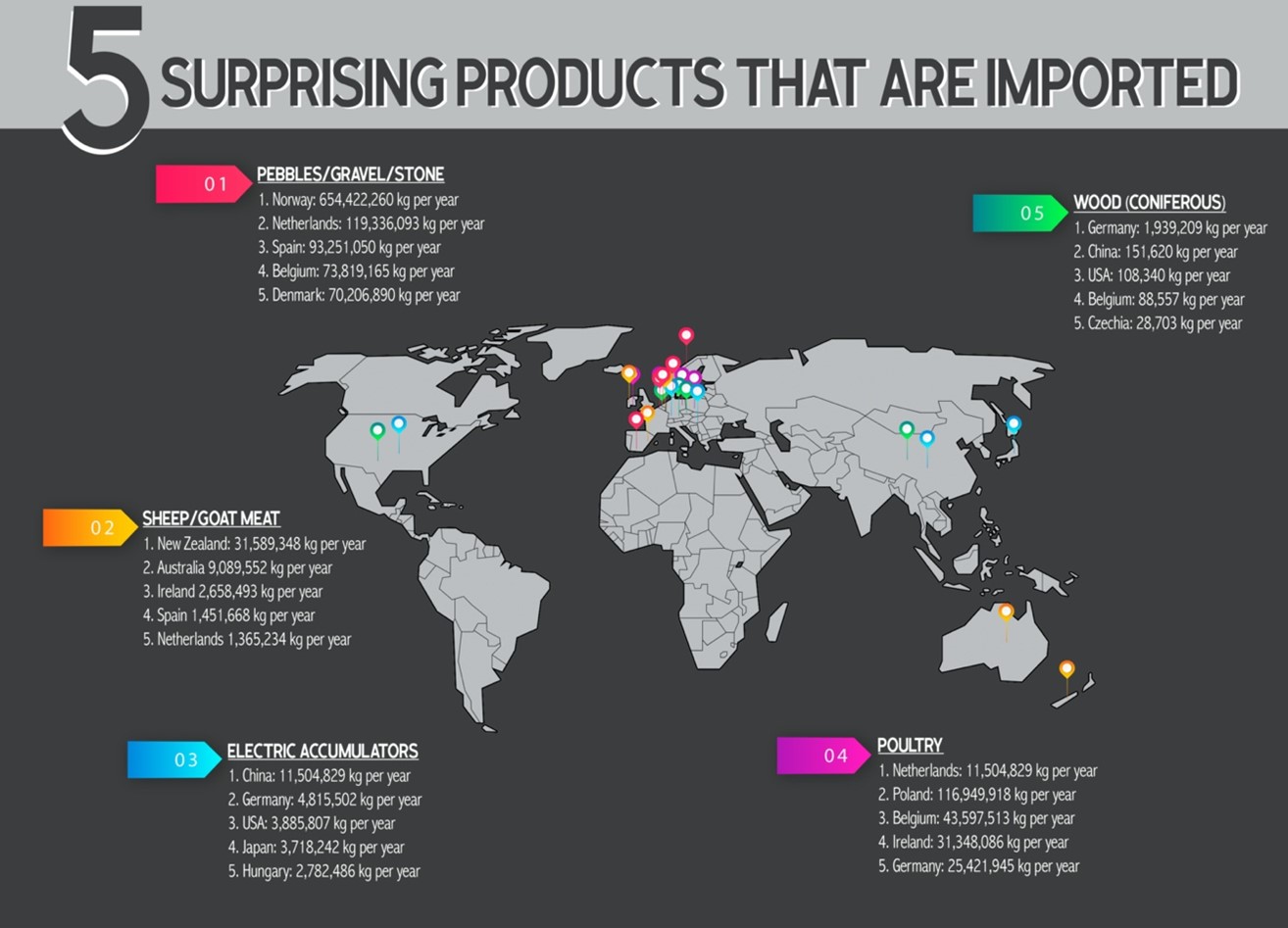

We are aware of some of our imports such as fruit and veg due to their labelled packaging, but many of our imported goods are much more surprising. The graphic above shows five products that are heavily imported to the UK each year, and the top five countries that we import them from.

Electric accumulators, often referred to as secondary batteries, are a form of rechargeable energy storage. Most of us might be familiar with this form of energy storage as this is what powers our phones and other devices, but our heavy reliance on these imports is perhaps overlooked.

I don’t know about you, but as someone who lives in a town surrounded by sheep, it seems mindboggling that we’re importing 31 million kg of meat per year - from New Zealand alone!

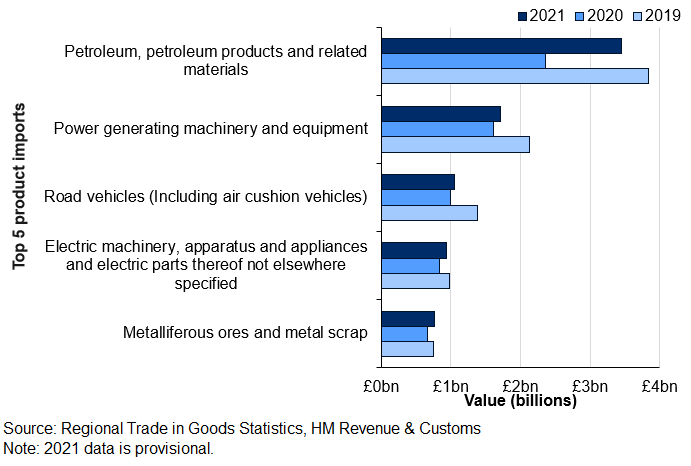

According to HMRC, the top imported product to Wales in 2021 was petroleum, followed by power generating machinery and road vehicles. Petroleum imports seem to be on the rise, largely from Algeria and Nigeria, but the impact this has in these countries isn’t often given much thought. Algeria has the third highest greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Africa, and as most of their fuel is exported elsewhere, this contributes even further to their high emissions (read more here).

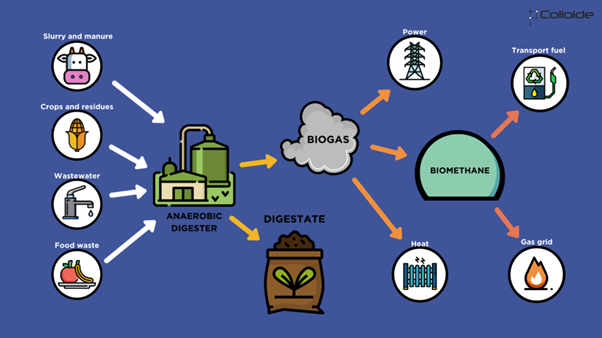

As agriculture moves towards the target of net zero by 2050, green fuels have been suggested as alternatives to petrol and diesel. Ammonia and methane are highly produced in the UK agriculture sector and can be used as alternative fuels. Better yet, hydrogen can be extracted and used in fuel cells.

Livestock creates a lot of poo (UK cows produce 36m tonnes of waste each year!). This excess poo could be used in a process known as anaerobic digestion which breaks down organic matter, capturing methane for us to use as fuel. This circular way of thinking not only encourages domestic-powered electricity and heat, it also aims to lower the carbon footprint in the process.

Another imported product that we heavily rely on in the UK is fertiliser. The Netherlands are our top supplier, with a 2021 trade value of roughly over £1billion! In weight, that equates to roughly 606,215,765 kg in just one year (nitrogenous and animal/vegetable based). Russia is the next supplier, followed by Belgium, Germany and Egypt (check out the data here). As the global production of fertilisers is responsible for roughly 1.4% of annual CO2 emissions, and prices continue to rise, it might be time to rethink our reliance on overseas imports.

The Welsh Government are closely monitoring the current high cost of fertiliser and have provided advice, particularly for farmers, to help try and mitigate the impact of highly priced fertiliser. As Welsh land provides excellent conditions for rearing livestock through grass utilisation, correct management of grassland, water and soils could help bring down the need for large amounts of inputs – ultimately helping bring down the cost AND demand for imported goods.

This is where poo comes in again – hear me out. Every 40 tonnes of muck that is applied, potentially saves £451 per hectare of land in fertiliser costs. A switch in manure applications in the spring, could also reduce nitrogen pollution by as much as 60%. The AHDB (Agricultural and Horticultural Development Board) are continuing to work with Defra and the Environment Agency, evolving their rules and guidance to help growers.

Now, by no means can our consumption-based emissions solely be fixed with animal poo. It is important to remember that these processes are riddled with nuance, that, as individual consumers, we have little control over.

Of course it would be pretty silly to assume that we could create a perfect haven of crop growth and production, while we are often confined by climate conditions, soil quality and other abiotic factors.

But, the solutions may already exist.

According to the UK Food Security Report (2021), we are already generally self-sufficient when it comes to grain production, producing over 100% of domestic consumption of oats and barley. So, this would suggest that we have the means and suitable conditions to grow these crops. Despite this, in the same year this report was published, as ONS data reveals, we still imported £130 million worth of grain (wheat, maize, barley) from Ukraine alone. Supply chains were majorly disrupted due to the ongoing Russia invasion – a stark example of how sensitive overseas supply chains can be in times of conflict.

As many solutions already exist, wouldn’t it be great if we could rethink our approach to importing goods? As a whopping 25% of Welsh GHG emissions are from imported goods, minimising the consumption of carbon intensive imports could really go a long way in contributing to decarbonisation. At the same time, domestic solutions would only boost jobs and stimulate the Welsh economy.

A wise man once said, “with great power comes great responsibility”, and now more than ever it is vital for those in power to be responsible in our approach to consumption. If we are to be a global leader on climate change, we must take responsibility for global emissions that are caused by UK demand.